Python's eval() function is one of the language's most powerful yet controversial features. This built-in function allows developers to execute arbitrary Python expressions from strings at runtime, opening up possibilities for dynamic code execution while simultaneously introducing significant security considerations. This comprehensive guide explores the capabilities, practical applications, limitations, and security best practices when working with eval in Python applications.

Understanding Python's eval() Function

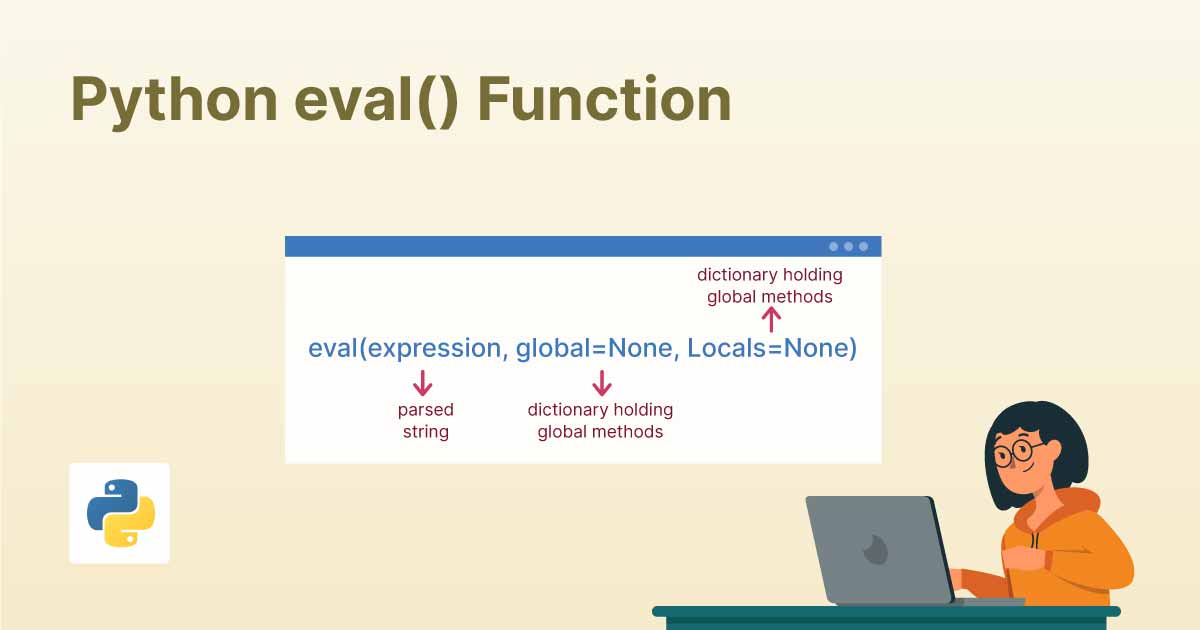

At its core, Python's eval() function evaluates a string as a Python expression and returns the result. Its syntax is straightforward:

eval(expression, globals=None, locals=None)

Where:

expression: A string containing a valid Python expressionglobals(optional): A dictionary to use as the global namespace during evaluationlocals(optional): A dictionary to use as the local namespace during evaluation

The function interprets and executes the string as Python code within the current interpreter, using the provided namespaces or the caller's namespaces if none are specified.

Basic Usage Examples

Let's start with some simple examples to demonstrate how eval() works:

# Basic arithmetic

result = eval('2 + 2 * 3')

print(result) # Output: 8

# Using variables from the current scope

x = 10

y = 5

result = eval('x * y + 2')

print(result) # Output: 52

# Using built-in functions

result = eval('len("hello")')

print(result) # Output: 5

# List comprehension

result = eval('[x**2 for x in range(5)]')

print(result) # Output: [0, 1, 4, 9, 16]

Practical Applications of eval()

Despite its security concerns (which we'll address later), eval() offers several legitimate and powerful use cases in Python development:

1. Dynamic Mathematical Expressions

One of the most common applications is evaluating mathematical expressions provided by users:

def calculator(expression):

# Only allow safe mathematical operations

allowed_names = {"abs": abs, "pow": pow, "round": round, "int": int, "float": float}

allowed_symbols = {"+", "-", "*", "/", "**", "(", ")", ".", ","}

# Check if expression contains only allowed characters and names

for char in expression:

if char.isalpha() and char not in "".join(allowed_names):

raise ValueError(f"Character not allowed: {char}")

if not (char.isalnum() or char.isspace() or char in allowed_symbols):

raise ValueError(f"Character not allowed: {char}")

# Evaluate the expression with limited globals

return eval(expression, {"__builtins__": {}}, allowed_names)

# Example usage

result = calculator("abs(-19) + pow(2, 3)")

print(result) # Output: 27

2. Configuration Systems

eval() can be useful for configuration files where Python expressions offer more flexibility than static values:

config = {

"debug": True,

"log_level": "eval('DEBUG' if debug else 'INFO')",

"max_connections": "eval('100 if debug else 500')",

"data_directory": "'/tmp/debug' if debug else '/var/data'",

}

# Process configuration

processed_config = {}

for key, value in config.items():

if isinstance(value, str) and value.startswith("eval("):

# Extract the expression from eval('...')

expr = value[5:-2] # Remove eval(' and ')

processed_config[key] = eval(expr, globals(), processed_config)

else:

processed_config[key] = value

print(processed_config)

# Output: {'debug': True, 'log_level': 'DEBUG', 'max_connections': 100, 'data_directory': '/tmp/debug'}

3. Dynamic Attribute Access

When dealing with nested attributes or dictionary keys based on string input:

class User:

def __init__(self):

self.profile = {"name": "John", "email": "[email protected]"}

self.settings = {"theme": "dark", "notifications": True}

user = User()

# Accessing nested attributes safely using eval

def get_attribute(obj, attr_path):

# Restrict access to only the object's attributes

safe_globals = {"__builtins__": {}}

safe_locals = {"obj": obj}

# Construct an expression that navigates object attributes

expr = "obj." + attr_path

try:

return eval(expr, safe_globals, safe_locals)

except Exception as e:

return f"Error accessing {attr_path}: {str(e)}"

print(get_attribute(user, "profile['name']")) # Output: John

print(get_attribute(user, "settings['theme']")) # Output: dark

4. Simple Template Systems

Creating basic templating systems for string formatting:

def render_template(template, **context):

# Add safe functions to the context

safe_context = {

"str": str,

"len": len,

"range": range,

"enumerate": enumerate,

**context

}

result = ""

for line in template.split('\n'):

if "{{" in line and "}}" in line:

# Extract expressions between {{ and }}

parts = []

remaining = line

while "{{" in remaining and "}}" in remaining:

prefix, remaining = remaining.split("{{", 1)

expr, remaining = remaining.split("}}", 1)

parts.append(prefix)

# Evaluate the expression in the given context

parts.append(str(eval(expr.strip(), {"__builtins__": {}}, safe_context)))

parts.append(remaining)

result += "".join(parts) + "\n"

else:

result += line + "\n"

return result.rstrip('\n')

# Example usage

template = """

Hello, {{ name }}!

You have {{ len(items) }} items in your cart.

{% for i, item in enumerate(items) %}

{{ i+1 }}. {{ item }} - ${{ prices[item] }}

{% endfor %}

Total: ${{ sum(prices[item] for item in items) }}

"""

data = {

"name": "Alice",

"items": ["Apple", "Banana", "Orange"],

"prices": {"Apple": 1.20, "Banana": 0.50, "Orange": 0.75}

}

# This is a simplified example that would need additional processing

# for the {% for %} loop syntax

Alternatives to eval()

Before reaching for eval(), consider these safer alternatives that might meet your needs:

1. ast.literal_eval()

For evaluating literal expressions like strings, numbers, lists, dicts, etc., the ast.literal_eval() function provides a safer alternative:

import ast

# Safe evaluation of literals

data = ast.literal_eval('{"name": "John", "age": 30}')

print(data) # Output: {'name': 'John', 'age': 30}

# Will raise an exception for expressions with operations

try:

ast.literal_eval('2 + 2') # This will fail

except ValueError as e:

print(f"Error: {e}")

2. Custom Expression Parsers

For mathematical expressions, specialized parsers like sympy offer safer alternatives:

from sympy.parsing.sympy_parser import parse_expr

from sympy import symbols, sympify

x, y = symbols('x y')

expr = parse_expr('x**2 + 2*x*y + y**2')

result = expr.subs({x: 2, y: 3})

print(result) # Output: 49

3. String Template Substitution

For simple templating needs, Python's string formatting or the Template class works well:

from string import Template

# Using Template

t = Template('Hello, $name! You are $age years old.')

result = t.substitute(name='Alice', age=30)

print(result) # Output: Hello, Alice! You are 30 years old.

# Using f-strings (Python 3.6+)

name, age = 'Bob', 25

result = f'Hello, {name}! You are {age} years old.'

print(result) # Output: Hello, Bob! You are 25 years old.

Security Risks of eval()

The power of eval() comes with significant security implications that developers must understand:

Code Injection Attacks

The most severe risk is code injection, where malicious input can execute arbitrary code:

# DANGEROUS - Never do this with user input!

user_input = "open('/etc/passwd').read()"

result = eval(user_input) # This would read system files!

System Access

Without proper restrictions, eval() can access system functions:

# DANGEROUS - Grants access to system operations

user_input = "__import__('os').system('rm -rf /')"

eval(user_input) # Could attempt to delete system files!

Resource Consumption

Malicious input could consume excessive resources:

# DANGEROUS - Could cause a denial of service

user_input = "['x' * 1000000 for _ in range(1000)]"

eval(user_input) # Creates a massive list, potentially crashing the application

Security Best Practices

If you must use eval(), follow these security practices to minimize risks:

1. Restrict the Execution Environment

Always provide custom globals and locals dictionaries that contain only what's necessary:

def safe_eval(expr):

# Empty __builtins__ prevents access to built-in functions

safe_globals = {"__builtins__": {}}

# Only provide the functions and variables needed

safe_locals = {

"abs": abs,

"max": max,

"min": min,

"sum": sum,

"len": len,

}

return eval(expr, safe_globals, safe_locals)

2. Input Validation

Always validate and sanitize input before passing it to eval():

import re

def is_safe_expression(expr):

# Only allow alphanumeric characters, basic operators, and spaces

pattern = r'^[a-zA-Z0-9_\+\-\*\/\%\(\)\[\]\{\}\,\.\s]*$'

return bool(re.match(pattern, expr))

def safe_calculator(expr):

if not is_safe_expression(expr):

raise ValueError("Invalid expression")

# Proceed with restricted eval

return safe_eval(expr)

3. Use Timeouts

Implement timeouts to prevent resource exhaustion attacks:

import signal

class TimeoutError(Exception):

pass

def timeout_handler(signum, frame):

raise TimeoutError("Evaluation timed out")

def safe_timed_eval(expr, timeout=1):

# Set the timeout

signal.signal(signal.SIGALRM, timeout_handler)

signal.alarm(timeout)

try:

result = safe_eval(expr)

signal.alarm(0) # Disable the alarm

return result

except TimeoutError as e:

raise e

finally:

signal.alarm(0) # Ensure the alarm is disabled

Note: This timeout approach works on Unix-based systems but not on Windows.

4. Consider Sandboxing

For critical applications, consider running the eval() operation in a separate process with restricted permissions:

import subprocess

def sandbox_eval(expr):

# Create a Python script that evaluates the expression in a safe environment

script = f"""

import ast

try:

# Only allow literal evaluation

result = ast.literal_eval('{expr.replace("'", "\\'")}')

print(result)

except Exception as e:

print(f"Error: {{e}}")

"""

# Run in a separate process

result = subprocess.run(

["python", "-c", script],

capture_output=True,

text=True,

timeout=2

)

return result.stdout.strip()

Understanding Related Functions

Python offers two other functions similar to eval() that are worth understanding:

exec()

While eval() evaluates a single expression and returns its value, exec() executes Python code as statements without returning a value:

# exec() executes statements

exec("x = 10; print(x)") # Outputs: 10

# No return value

result = exec("x = 10")

print(result) # Outputs: None

compile()

The compile() function pre-compiles Python code for later execution:

# Compile expression mode

expr_code = compile("2 + 2", "<string>", "eval")

result = eval(expr_code)

print(result) # Outputs: 4

# Compile statement mode

stmt_code = compile("x = 5; y = x * 2", "<string>", "exec")

namespace = {}

exec(stmt_code, namespace)

print(namespace) # Outputs: {'x': 5, 'y': 10}

Advanced Techniques and Considerations

Creating Domain-Specific Languages (DSLs)

eval() can be useful for implementing simple domain-specific languages:

class QueryLanguage:

def __init__(self, data):

self.data = data

def execute(self, query):

safe_globals = {

"__builtins__": {

"len": len,

"sum": sum,

"min": min,

"max": max,

"list": list,

"dict": dict,

"set": set

}

}

safe_locals = {

"data": self.data,

"filter": filter,

"map": map

}

return eval(query, safe_globals, safe_locals)

# Example usage

database = [

{"id": 1, "name": "Alice", "age": 30},

{"id": 2, "name": "Bob", "age": 25},

{"id": 3, "name": "Charlie", "age": 35},

{"id": 4, "name": "David", "age": 28}

]

query_engine = QueryLanguage(database)

# Simple query to filter users older than 27

result = query_engine.execute("list(filter(lambda x: x['age'] > 27, data))")

print(result) # Outputs filtered users

# Calculate average age

result = query_engine.execute("sum(item['age'] for item in data) / len(data)")

print(result) # Outputs: 29.5

Performance Considerations

While python eval provides flexibility, it has performance implications:

- Compilation Overhead: Python must parse and compile the string at runtime

- Namespace Lookups: Variable lookups may be slower in the dynamic environment

- Optimization Limitations: The Python interpreter cannot apply certain optimizations

For performance-critical code that requires frequent evaluations, consider pre-compiling expressions:

import time

# Function to measure execution time

def measure_time(func, *args, **kwargs):

start = time.time()

result = func(*args, **kwargs)

end = time.time()

return result, end - start

# Direct calculation

def direct():

result = 0

for i in range(1000000):

result += i * 2

return result

# Using eval each time

def using_eval():

result = 0

for i in range(1000000):

result += eval(f"{i} * 2")

return result

# Using pre-compiled expression

def using_compile():

result = 0

code = compile("i * 2", "<string>", "eval")

for i in range(1000000):

result += eval(code, {"i": i})

return result

# Compare performance

direct_result, direct_time = measure_time(direct)

print(f"Direct calculation: {direct_time:.6f} seconds")

eval_result, eval_time = measure_time(using_eval)

print(f"Using eval(): {eval_time:.6f} seconds")

compile_result, compile_time = measure_time(using_compile)

print(f"Using compile(): {compile_time:.6f} seconds")

Typically, direct calculation is fastest, followed by pre-compiled expressions, with repeated eval() calls being the slowest.

Python's eval() function offers remarkable power and flexibility for dynamic code execution, enabling sophisticated applications like mathematical expression evaluators, configuration systems, and simple domain-specific languages. However, this power comes with substantial security risks that must be carefully managed.

For many use cases, safer alternatives like ast.literal_eval(), specialized parsers, or template systems provide better security with adequate functionality. When eval() is truly necessary, following strict security practices—limiting the execution environment, validating input, implementing timeouts, and considering isolation techniques—can help mitigate risks.